Fertility rates have fallen everywhere outside of sub-Saharan Africa. And they have fallen faster, and dropped even further, in some developed nations than others.

In a new paper, Claudia Goldin, the Henry Lee Professor of Economics, explains this divergence with a data-tested model that shows gendered and generational conflicts arising with swift economic change. The 2023 Nobel laureate notes countries whose economies grew gradually over the 20th century — including the U.S. and Sweden — now average around 1.7 children born to each woman. However, latecomers to development like Japan, Korea, and Italy average far fewer children.

The study illustrates how women in transitioning modern economies can be especially disadvantaged by traditional gender roles. “Children take time, and that time isn’t easily contracted out or mechanized,” said Goldin in a presentation of the research to the European Central Bank’s Annual Research Conference last fall. “Therefore much of the change in fertility will depend on if men assume more work in the home as women are drawn into the market, particularly if the home has children.

“If they don’t,” she continued, “women will be forced to cut back on something.”

Claudia Goldin.

File photo by Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Her analysis builds upon findings from a 2009 study published in the Journal of Economic Perspectives titled “Will the Stork Return to Europe and Japan?” The paper — by economists James Feyrer, Bruce I. Sacerdote, Ph.D. ’97, and Ariel Dora Stern, Ph.D. ’14 — found birthrates are highest in countries with low-income levels and low female employment. But a surprising pattern was observed in wealthier countries.

“They note that women’s participation in the economy is actually greater in countries with higher fertility,” said Goldin, who is also the Lee and Ezpeleta Professor of Arts and Sciences.

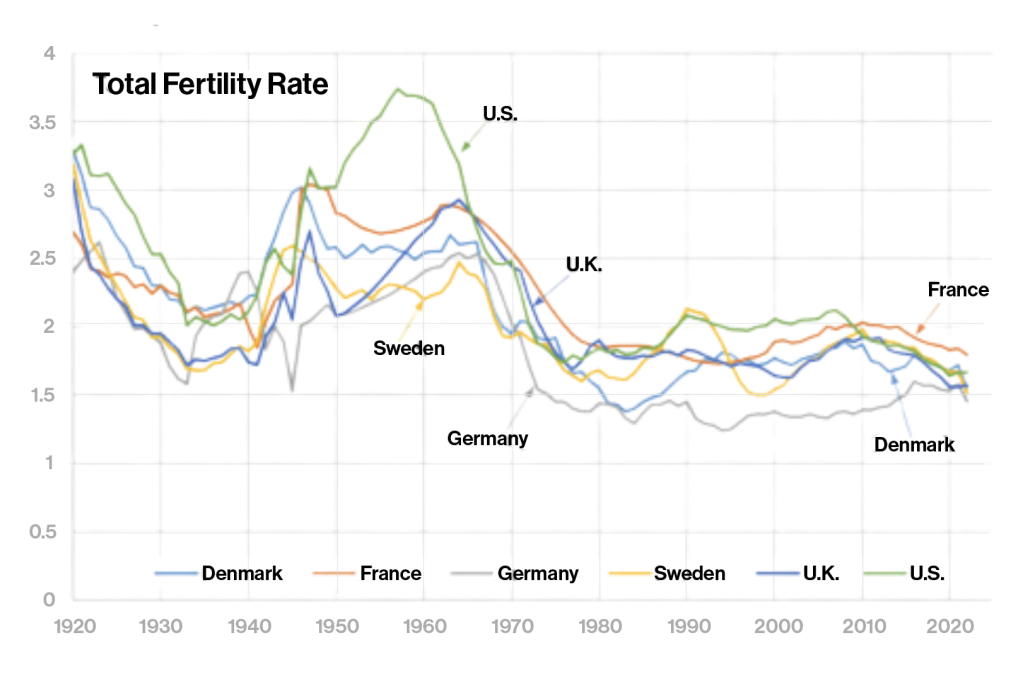

Her paper compares fertility rates in two groups of six countries. The first set — comprised of Denmark, France, Germany, Sweden, the U.K., and the U.S. — saw relatively continuous economic development over the 20th century even with the disruptions of the Great Depression and two world wars. All had reached a total fertility rate of around two children per woman by the 1970s. Not until the 2010s did rates fall below that figure.

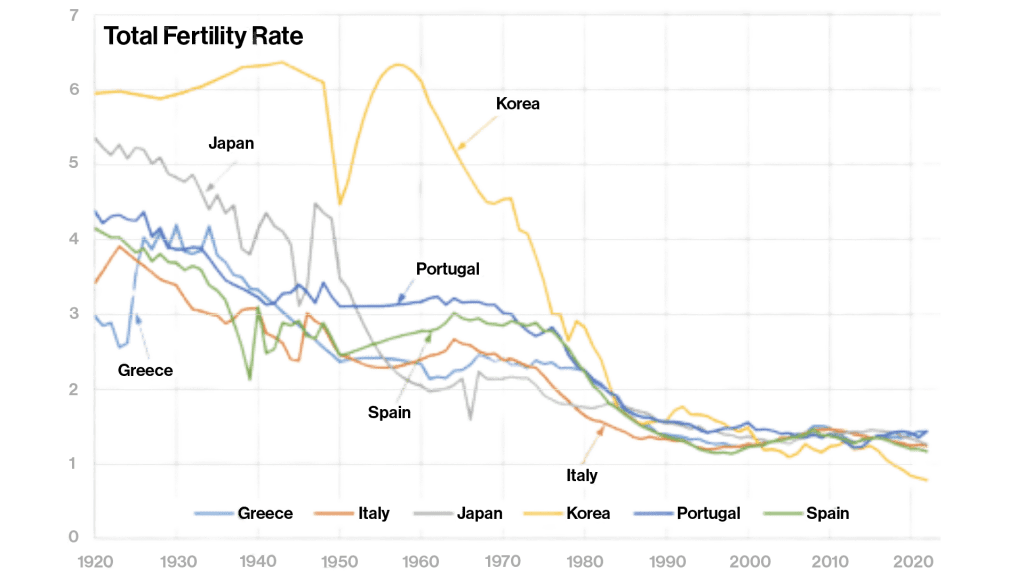

The second group — Greece, Italy, Japan, Korea, Portugal, and Spain — developed quickly from the mid-1950s and ’60s after long periods of economic stagnation or decline. Each averaged three children or more per woman in 1970. But all six had dropped below two by the mid-1980s. Most had converged to around 1.3 by the mid-1990s, with Korea being the extreme case. Its total fertility rate for 2022 (the last year included in Goldin’s analysis) was 0.78 children per woman.

Demographers have dubbed the fertility rates of those nations the “lowest-low.”

Total fertility rates for two groups of nations, 1920 to 2022

Goldin theorized that families in the second set of countries had been “catapulted” into the modern economy, with less time for adjusting gender norms. Korea, for example, saw incomes quadruple between the 1960s and ’80s, with 30 percent of the population moving from rural areas to urban areas (usually Seoul) over the same period.

“Rapid economic change often challenges strongly held beliefs,” she summarized. “And beliefs change more slowly than economies do.”

Her paper introduces a framework for understanding how such conflicts lead to lower fertility. It assumes that family traditions and beliefs inform a person’s fertility plans. But so do economic conditions observed in young adulthood. This all comes together as couples plan family size, with men putting more weight on factors inherited from previous generations and women acting as “agents of change” by emphasizing economic self-interest.

“It’s not that boys are more traditional than girls; it’s that boys have more to gain from the traditional home,” Goldin explained. “But girls suddenly see that their options have changed. They can get an education. They can go out and work.”

Goldin’s model demonstrates that greater macroeconomic growth from childhood to adulthood means greater generational conflict and wider gulfs between men’s and women’s preferred family size. It assumes that men who contribute more at home have more of an influence on family size. But women’s desires win out when caregiving and other household tasks fall primarily on them.

Goldin’s model demonstrates that greater macroeconomic growth from childhood to adulthood means greater generational conflict and wider gulfs between men’s and women’s preferred family size.

To test her ideas, Goldin started with 100 years of economic and geographic data from all 12 countries. Sure enough, the “lowest-low” nations saw meteoric growth in per-capita gross domestic product, combined with huge rural-to-urban migrations, beginning in the mid-20th century. Meanwhile, GDP charted a slow, steady incline in the first set of countries, with far fewer migrations to big cities.

Time-use surveys, assembled by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, provided Goldin with evidence of gendered divisions of unpaid caregiving and household labor between 2009 and 2019. She uncovered a bigger gap between men and women in the “lowest-low” countries. Women, on average, devoted 3.1 more hours per day to household duties in Japan and three more hours per day in Italy. Compare that with the U.S., where women logged about 1.79 more daily hours on household duties, or Sweden, where the difference was just 0.8 hours.

“The bottom line is,” Goldin said, “countries that saw this very, very rapid increase in standards of living are probably at sub-optimal birthrates.”

The labor economist and economic historian ends by floating a novel solution. The U.S. baby boom, which peaked above 3.5 children per woman in the late 1950s, is the rare example of a wealthy country temporarily increasing its fertility rate. It was accomplished by “glorifying marriage, motherhood, the ‘good wife,’ and the home,” Goldin writes.

Societies that want to encourage more babies today, she suggests, should try venerating fatherhood.

Source link